Estimated reading time: 11 minutes

What happened at COP26, and what does the Glasgow Climate Pact mean for public health? Where will public health sit in future climate change negotiations?

Welcome to the COP

“I see a lot of worried faces. Everyone looks very serious” says a woman in the street, handing out leaflets about war and fossil fuels. Nearby, another woman on a makeshift stage makes a passionate plea for survival on behalf of indigenous people all over the world. Life, death, survival, and the quality of lives we will lead are in question. It is 8am on Wednesday, 10 November 2021 and this is COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland. The first version of the text which will eventually become the Glasgow Climate Pact has just been published.

Each line is being analysed to understand what has been won and what has been lost. Under cold grey skies, delegates rush to the entrance halls as they plan their next negotiation strategies. At this point, few people could predict the dramatic scenes that would unfold in the coming days. This global meeting will almost fail. Negotiators will only rescue the deal in tearful scenes close to midnight, more than a day after world leaders were due to get back into their jets.

The decisions made here are issues of survival on a global scale. But we will feel many of the impacts on national, local, and individual levels. At this conference, health has loomed larger than in previous debates on the climate crisis.

In Europe, the tide is changing. There is greater recognition that climate change will dramatically affect our health. Questions are being asked about how to mitigate the health effects of the floods, fires, and heatwaves already causing immense loss and suffering in Europe today. But further, what can we do to stop it from getting worse?

From Paris to Glasgow

To understand what happened in Glasgow and what it means for public health, we must first understand what happened in Paris in 2015 at COP21, and the resulting Paris Agreement.

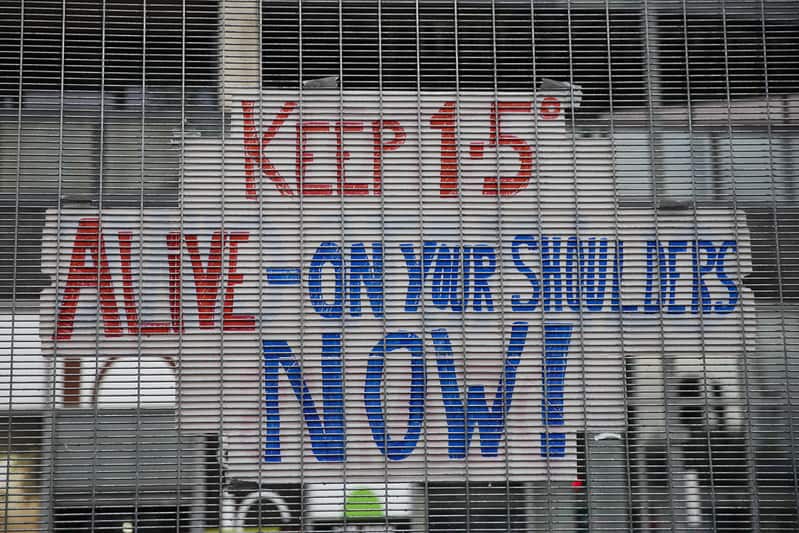

Back then, a landmark agreement was struck: every country agreed to work together towards limiting global warming to well below 2 degrees, and to aim for 1.5 degrees. Each fraction of a degree of warming will lead to heavy loss of life and livelihoods. The slogan “1.5 to stay alive” soon became a haunting reminder of what is at stake. At the conference, countries committed to set out their increasingly ambitious plans to tackle climate change every 5 years from then.

2020 was, therefore, the first deadline for countries to show how they would deliver on their promises. They were due to present their ‘Nationally Determined Contributions’, known as NDCs. The pandemic delayed the process, and COP26 was held instead in 2021, instead of 2020. There were other issues on the table in Glasgow – the Paris Agreement left many questions unanswered.

Countries entered the negotiations for COP26 with four stated aims:

- Secure global net zero by mid-century and keep 1.5 degrees within reach. That meant providing emissions reductions targets for 2030 which would allow us to reach net zero by 2050

- Adapt to protect communities and natural habitats. This means building resilient systems that can protect lives and prevent harm.

- Mobilise finance. Developed countries had promised to mobilise at least $100bn USD in climate finance per year by 2020. At COP26, countries were supposed to show how they would deliver on this promise – but would fail to do so.

- Work together to deliver. This meant finalising the ‘Paris Rulebook’ that would govern the Paris agreement.

The climate crisis and public health

The climate crisis is, clearly, a public health issue. It is linked to social and environmental determinants of health.

We see these links in, for example, deaths and illnesses related to extreme weather events such as flooding, fires, and heatwaves. It is connected to respiratory and cardiovascular disease. It will affect how water- and air-borne diseases spread. There will be mental and social effects; environmental devastation, losing one’s homes and families will naturally affect our ability to live well. Beyond this, we must consider how we will live in a world affected by conflict and migration linked to increasingly scarce resources.

An issue of health equity

There is an equity dimension to consider too. The negative health effects of climate change will fall heaviest on our most vulnerable neighbours. They already experience inequalities in health outcomes linked to the environment. In Europe today, it is the poorest amongst us that live with the worst air pollution, who live in homes ill-equipped to deal with extreme temperature changes and who are most vulnerable to fuel price fluctuations. On a wider scale, it is the least educated and most vulnerable to unemployment who may see their jobs in polluting industries disappear as we transition to green economies. They will feel the health impacts of unemployment.

There are further concerns that the lifestyle changes required to mitigate climate change will be unafordable, leading to bigger gaps between the ‘haves and have-nots’. For example, access to quality food, fluctuations in the costs of ‘living green’, and the costs of lower-carbon transport

Health, equity, and climate change can be considered as inextricable issues. Solutions to address the three issues together exist – this was one of the core issues explored by the INHERIT project, as many of the climate mitigation strategies will produce clear co-benifits for public health.

Health in the negotiations

The Glasgow Climate Pact is the result of COP26 and represents what was agreed. It acknowledges the importance of health early on. The second paragraph describes the pandemic, and the need for a sustainable and inclusive recovery. The fourth paragraph explicitly acknowledges the right to health.

Health had a radically different – and more important – place in the 2021 negotiations than in previous COP processes. There are several reasons behind this.

Health as a science priority area

For one, the UK presidency designated health a ‘science priority area’ in the negotiations. They worked with organisations such as the World Health Organisation (WHO), Healthcare Without Harm, and Greener NHS on a COP26 Health Programme. This programme recognised that climate change affects health and health inequalities, that the positive health outcomes found in addressing climate change can motivate stronger action, that making health systems low-carbon can lead to significant reductions in emissions, and that resilient health systems can better protect people. The health programme had 5 priorities:

- Building climate resilient health systems.

- Developing low carbon sustainable health systems.

- Adaptation research for health.

- The inclusion of health priorities in Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)

- Raising the voice of health professionals as advocates for stronger ambition on climate change.

The health argument for climate action

Ahead of the conference, the WHO sought to reflect the views of the public health community on climate change, and to make arguments for and stress the urgency of action on climate change. The result was the ‘COP26 special report: The health argument for climate action’. It makes 10 recommendations:

- Commit to a healthy recovery.

- Our health is not negotiable. Place health and social justice at the heart of the UN climate talks.

- Harness the health benefits of climate action.

- Build health resilience to climate risks.

- Create energy systems that protect and improve climate and health.

- Reimagine urban environments, transport, and mobility.

- Protect and restore nature as the foundation of our health.

- Promote healthy, sustainable, and resilient food systems.

- Finance a healthier, fairer, and greener future to save lives.

- Listen to the health community and prescribe urgent climate action.

Prescription for a healthy climate

Pressure for more action on the links between climate and health came from people within health systems. A ‘Healthy Climate prescription’ has now been signed by over 450 organisations (including EuroHealthNet) representing over 45 million health workers, together with over 3,400 individuals from 102 different countries. This urgent call for climate action comes from medical practitioners, the public health workforce and more. They see that climate change is already affecting the people that they aim to protect and cure. They recognise that health systems themselves need to be decarbonised to prevent a vicious cycle. This letter was supported by the Global Climate and Health Alliance and the WHO

For the first time there was a health pavilion at the COP, hosted by the WHO. It enabled two weeks of events focused on health, and provided a meeting place for the health community at the COP.

Expectation vs Delivery

The health programme

The organisers of the health programme can claim some success. Their efforts focused on the first two areas of the health programme: ‘Commitment 1: Climate resilient health systems’ and ‘Commitment 2: Sustainable low carbon health systems. A total of 51 countries have signed up to those commitments. Some have made commitments to develop ‘net zero’ health systems, and some of those countries have further offered dates for when they will reach net zero. The first group aim to reach their goal by 2030, while others have given themselves until 2050.

Only five out of twenty-seven EU countries signed up to any commitments:

- Belgium

- Germany

- Ireland

- The Netherlands

- Spain

Norway and the UK also made committments.

Health in the Glasgow Climate Pact

When we look at the Glasgow Climate Pact as a whole, it is hard to make claims of success on health.

Countries came to Glasgow to explain how they would deliver on their promises to limit global heating to 1.5 degrees. This is the limit for catastrophic human impacts but will still lead to immense suffering and ill-health. The NDC pledges given at Glasgow – if they will be met – would take us to an estimated 2.4 degrees.

Fossil fuels, which are driving climate change, were a contentious issue at the conference. An early draft signalled the possible end to fossil fuel subsidies, but some countries fought against this in the closing hours of negotiations. They argued that the green transition should be a just one; committing to fast energy transitions would, they said, not allow them to protect their countries tackle some of the immediate threats which their populations face. Even though the use of coal accounts for 40% of annual CO2 emissions, the final text on the issue was weak. Parties agreed to ‘accelerating efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, while providing targeted support to the poorest and most vulnerable in line with national circumstances and recognizing the need for support towards a just transition.’

Finally, global failure to mobilise financing to address climate change will limit progress and leave some nations struggling.

Better weather ahead?

We do still have reasons to be positive about the future. Thanks to the work of international organisations, health bodies, and the health workforce, health now has a place at the negotiating table. Parties are increasingly aware of the links between climate change and health. Momentum is building, and the health community has an opportunity to mobilise and see real change. We face connected challenges : protecting and promoting health in a rapidly changing world, improving health equity, and managing climate change. If the health community will continue to demonstrate these connections, there is an opportunity to make progress on multiple fronts.

Global

On a global level, the WHO will continue to work on these issues, and the global climate and health alliance, of which EuroHealthNet is a member, will continue to work on global advocacy. IANPHI has recently published a Roadmap for Action on Health and Climate Change

Europe

In Europe, we can expect to see legislative changes, for example on

- Updated air pollution rules

- European Green Deal

- Social Climate Fund

- European Climate pact

- Innovation fund

- European Urban agenda

- Horizon Europe research mission on Climate Neutral and Smart Cities.

At the same time, the European Climate and Health Observatory will provide tools and other resources on climate and health.

EuroHealthNet has established the climate crisis as a strategic priority area for the next 5 years, and will continue to work on the topics through public health policy, practice, and research. EuroHealthNet’s partners – national and regional public health agencies – say they are already witnessing the effects of climate change and health. They are starting to implement innovative practices to mitigate and avoid worse outcomes. In November 2021, public health bodies came together to exchange on their work on climate change adaption and mitigation. This is the just the start of ongoing collaboration in the coming years. EuroHealthNet is now an official observer to the UNFCCC process, and will continue to monitor and support global developments and negotiations.

Further reading and resources

- EuroHealthNetStatement: Our health is at risk if COP26 conclusions do not seize opportunities for a healthy, fairer future

- EuroHealthNet resources on public health, the climate crisis, and sustainability

- The European Climate and Health observatory

- WHO work on Climate change and health

- The Global Climate and health alliance

Alexandra is EuroHealthNet's Senior Communications Coordinator and the editor of EuroHealthNet magazine.

Her main areas of focus are health inequalities and the connections between health and climate change, employment, and ageing.

She is passionate about stories and the way we tell them, creating spaces for dialogue, and new forms of power and decision-making.

You can find her on twitter @AlexandraLatham