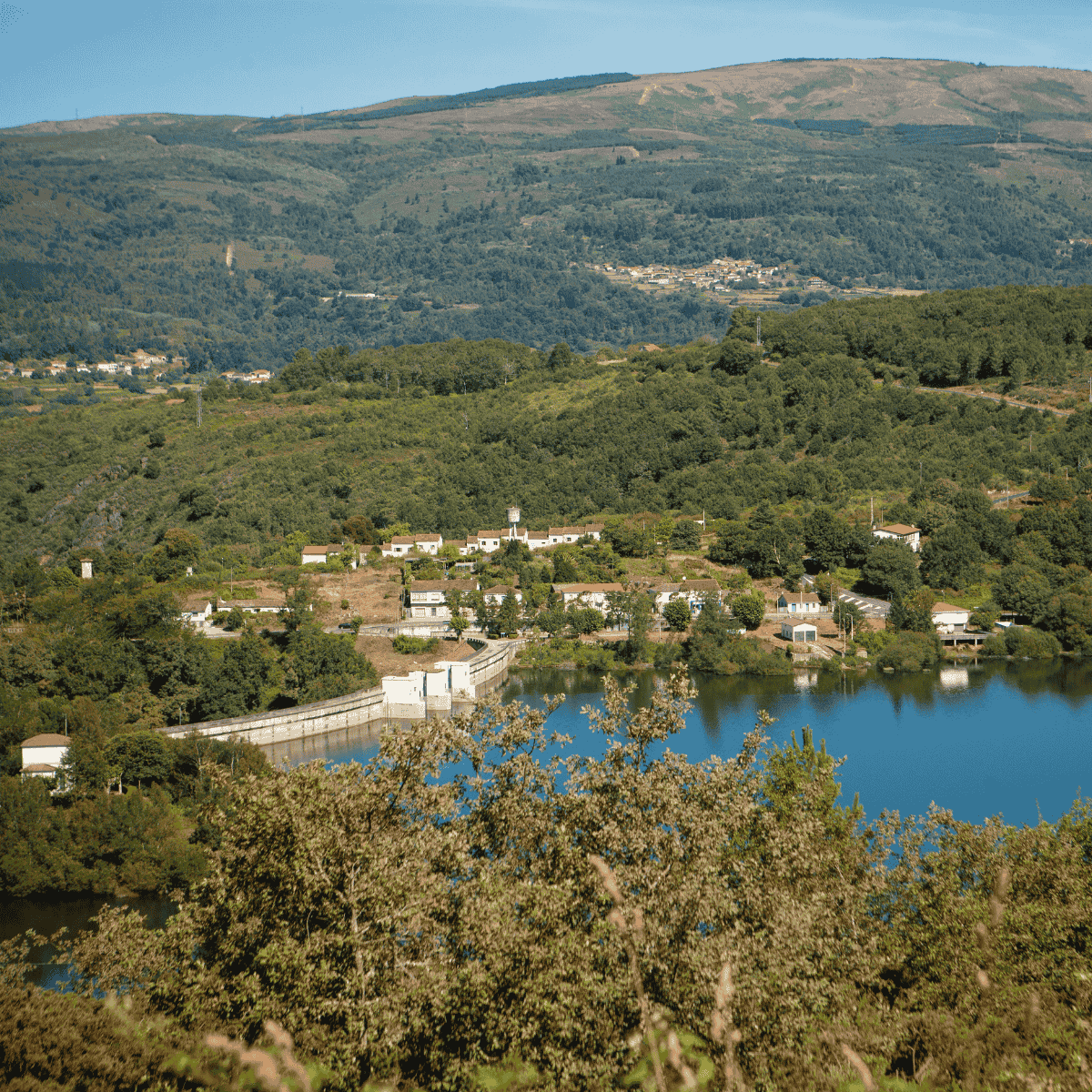

For 20,000 residents of the rural region of A Limia in Galicia, Spain, clean air and safe water were fast becoming luxury amenities. Families reported nausea, rising cancer risks, and untreatable infections from nitrate-contaminated wells and superbugs leaking from nearby factory farms. Now, a Spanish court has confirmed what these communities have long known, this is not just pollution, it is a violation of human rights and a stark health equity issue. In a landmark ruling, the High Court of Galicia confirmed the authorities had failed to protect the rights of residents, ordering urgent action to restore clean air and safe water.

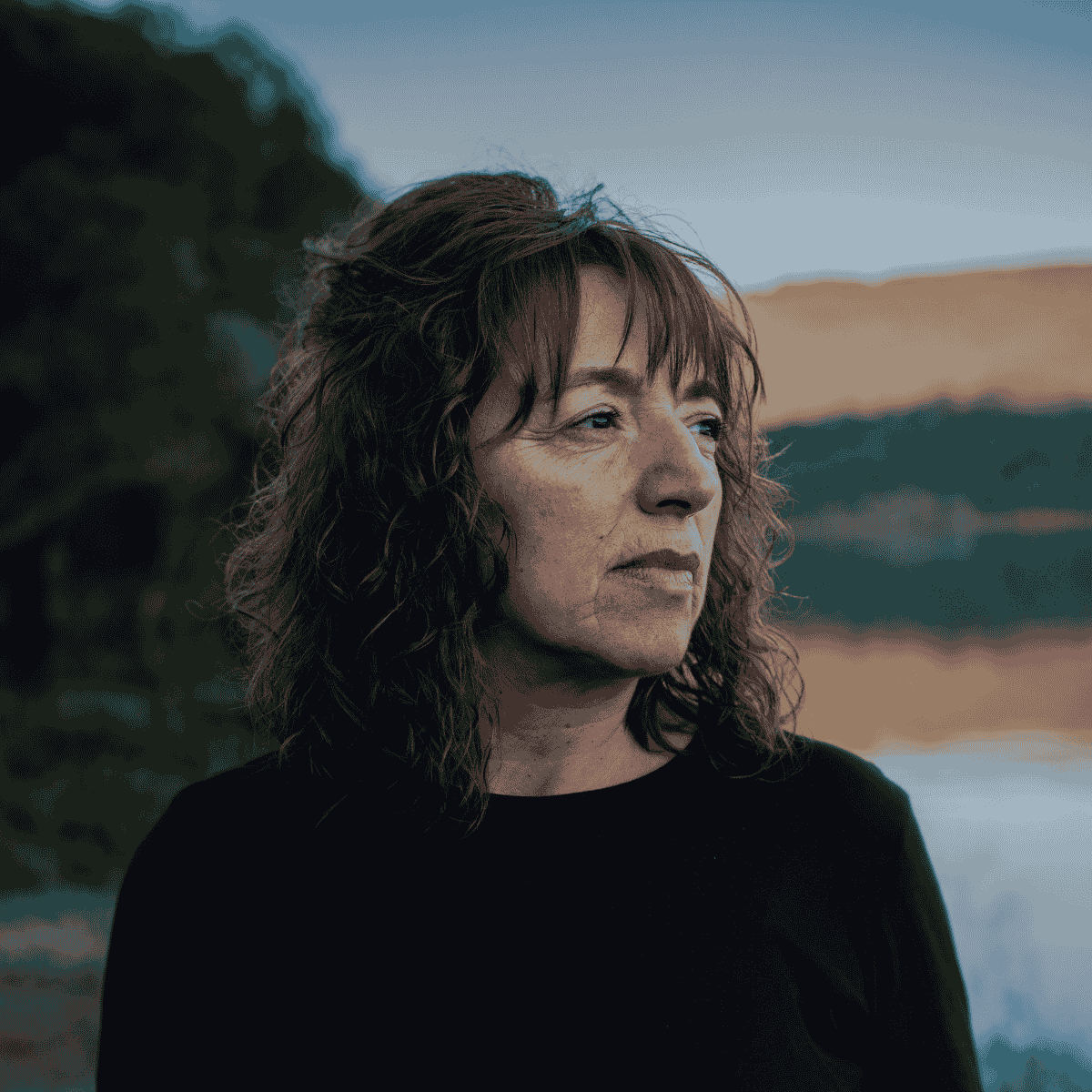

EuroHealthNet’s Ruth Thomas speaks with Malgorzata (Gosia) Kwiedacz-Palosz, a Senior Lawyer in the Fundamental Rights team at ClientEarth, to find out more.

Change rarely comes from staying silent. But in a time when politics feels like a tightrope walk without a safety net, how easy is it to truly speak up, to take a stand, to demand better? Having the means to raise your voice, to be heard, and to have support is a privilege in itself. Even here, in Brussels, the heart of Europe, many measure their words carefully, as many civil society organisations face harsh scrutiny. Right now, the air feels thick with caution. One phrase, one headline, can and sometimes has tipped the balance. But while silence may feel safe, it is a luxury only the least at risk can afford.

And yet, courage finds a way. This year, a landmark case reached the High Court of Galicia for the first time. Not led by the giants of power, but by those often overlooked, rarely heard. Who, you might ask? The community. Ordinary people who had had enough and wanted to make one thing clear - their health should never come after profit.

It’s early October, and I’m on my way to meet Malgorzata (Gosia) Kwiedacz-Palosz, a senior human rights lawyer at ClientEarth. Unlike many environmental organisations, ClientEarth doesn’t rely solely on campaigning or advocacy; it uses the law to confront the planetary crisis, tackling everything from climate change to biodiversity loss.

Across Europe, it’s almost entirely lawyer-staffed teams focus on specific areas, from agriculture to chemicals, applying their expertise to cases that can have far-reaching impact.

“Law provides the necessary tools and pressure to compel change. Scientific evidence identifies the problem, law provides the mechanism, and communities give the mandate to act. All three are needed,” Gosia explains.

The Galicia case

The case was a legal first as the High Court of Galicia ruled that extreme air and water pollution, caused by the vast expansion of intensive pig and poultry farming, breached residents' human rights. While the industrial installations caused the pollution, the court held the government accountable for failing to protect the health of its people. But this victory wasn’t won by lawyers alone. It was a triumph of ordinary people who didn’t want their health jeopardised any longer.

When we think about the environment, do we always remember that our health and wellbeing are inseparable from it? According to the World Health Organization, avoidable environmental risks are a major determinant of health in the European Region, estimated to account for nearly 20% of all deaths — at least 1.4 million lives every year. To put that into perspective, that’s the entire population of Hamburg lost every year – lost to avoidable environmental health risks.

In Galicia, the consequences were immediate and tangible. Residents were forced to stay indoors during the hot summer months, unable to enjoy the reservoir that had once been a gathering place. Algae and the stench from livestock runoff made swimming impossible. Headaches, fatigue, and nausea became daily realities.

This was no longer ‘just’ an environmental problem; this was now a health problem. An equity problem. Their right to life and health, Gosia emphasises, was “at imminent risk.”

“Around 20,000 residents, in the A Limia area of Galicia, no longer had clean air or safe water, these amenities were treated as luxuries rather than basic rights,” she continues.

The impact of the farms is still visible today. There are hundreds of industrial-scale pig and chicken installations in the area surrounding the small town, and every summer the reservoir becomes thick with algae, releasing a nauseating odour. Biodiversity has broken down as fish and small animals have disappeared, and residents can no longer enjoy the natural open spaces they once had – all of this in a country that faces extreme weathers as climate change grips it. Bars and shops have closed as tourists avoid the area, leaving the community trapped in what Gosia describes as a “sacrifice zone” for industrial activity. Faced with this reality, the community refused to accept it as normal.

Community action

But how did a group of civilians find themselves at the High Court, and win?

“The residents formed a local association to amplify their voices because individual complaints were ignored,” Gosia explains. “Despite submitting repeated requests to local authorities to monitor water quality, they were assured time and time again that everything was fine. Authorities weren’t taking their health seriously, prioritising profit over safety.”

The most vulnerable felt the consequences first and hardest. “Residents, many elderly, were deprived of social and community life. They couldn’t meet friends, enjoy nature, or visit family without suffering headaches, nausea, or fatigue. One resident even moved away due to health impacts, highlighting how environmental degradation affects both physical and mental wellbeing.”

What made this case remarkable was the scientific evidence that was available. Monitoring of water and air pollution, alongside biodiversity loss, showed authorities weren’t protecting residents. Gathering and analysing the data was time-consuming and expensive, but it made clear that health risks were real and immediate.

Health, equity, and the environment

Health is a fundamental human right. The very fact that I am writing this in 2025 shows how far we, as a society, still are from putting health before profit.

“I think we are lacking a holistic approach to the environment. It’s not enough to look at one thing in isolation, like soil contamination, or to rely only on paper assessments. Air and water quality also need to meet safe levels, and everything must be checked in real life, not just on paper,” continues Gosia.

Industries may cause the pollution, but it’s the authorities who decide what is permitted, what’s monitored, and what’s ignored. While people can feel when their air, water, or land is polluted, industries often shape perceptions, influence behaviour, and impact health in ways that make it harder for communities to recognise risks. If residents notice these threats but their voices are ignored, who gets to decide what a healthy environment should be?

Rural communities near industrial installations often lack the resources to move or fully understand the health risks they face. Authorities frequently fail to monitor environmental conditions, leaving residents exposed. Prevention is crucial, yet oversight is often insufficient.

“Regulations are fragmented, and authorities often fail to consider cumulative impacts. Industries must account for long-term environmental and health consequences, recognising that communities and future generations rely on these ecosystems,” Gosia explains. “Businesses and communities must collaborate, with awareness of long-term impacts. Education, transparency, and accountability can allow economies to thrive without compromising health.”

Industries monopolise the market, and we’re getting increasingly familiar with how they influence people’s health through advertising, but this case wasn’t about industry. This was about authorities needing to act and failing to do so.

“People living near industries often don’t question the risks because they rely on the jobs and assume the company is looking out for them. Authorities, however, tend to react only once harm has already occurred, instead of preventing it,” explains Gosia.

“In Galicia, we couldn’t conclusively say that anyone had yet been made seriously ill by the pollution, but the warning signs were obvious. The reservoir had lost its fish, and biodiversity had collapsed. Environmental and health impacts need to be assessed far more thoroughly when permits are granted, especially because many residents don’t have the digital literacy or technical background to understand complex industrial or legal documents,” she continues.

“It is the authorities who must evaluate growing impacts and protect people’s health. That is why this case is against the government, not the industry, as the legal responsibility for residents’ health lies with the state. The industry’s priorities are economic; it is not the industry’s responsibility to safeguard public health; the responsibility to protect people lies with the authorities.”

Access to nature and holistic health

Some communities are surrounded by parks and green spaces, while others have almost none. Access to nature is not equal, and its presence or absence matters for everyone.

“Health professionals should ask people, ‘Where do you live? What is your environment?’ Too often, when someone goes to the doctor with a headache, they are simply offered a painkiller. Understanding the conditions in which people live is crucial”, continues Gosia.

“If you live next to a motorway, your headaches might be linked to air pollution or noise. Doctors need to understand the source of the problem and the living conditions of their patients, not just treat symptoms."

“People can even monitor themselves. Air quality is trackable online. They can check if their health is changing because of pollution or water quality. Health professionals need to take these factors into account and assess them holistically.

“They should help people understand what they eat, where their food comes from, and how it affects them. It is not visible on packaging, but it matters deeply.”

Her advice to policymakers is simple. “Spend time with nature. Don’t underestimate it. Nature has a powerful effect on our health. Clean air and water should not be a luxury. They should be a basic right. Provide a healthy environment first and then focus on the rest.”

At the community level, Gosia encourages curiosity and proactive action: “If you notice something unusual, like a persistent bad smell or frequent headaches, check if it is connected to your environment. Don’t be afraid to request information from authorities about pollution near you.

“If one can win a case against a major corporation and even the government, it shows that change is possible. Communities and networks are key. You cannot act alone.

“Individuals need support. Form networks between affected people so no one feels alone. Try to work with and alongside public authorities and local government but insist on transparency and independent verification to ensure your health and rights are protected.” We need collaboration between experts, lawyers, citizens, and local associations to make a change.

“If it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a village to bring about environmental and social change”, she concludes.

Community leadership

Only those living in an environment can truly judge whether it meets their needs. Numbers and regulations alone are not enough; holistic, real-world assessment is necessary.

“Community leaders play a vital role in bridging this gap,” Gosia continues. “They translate scientific and legal information into accessible language and advocate for local needs. In Galicia, Pablo, the president of the local association, acted as a spokesperson. Trust, local knowledge, and collective action proved essential to empower residents.”

Courage of the community

Before I closed the interview, I wanted to understand the person behind the title. So, I set aside the legalities, and the politics to ask one final question: what drives you? What keeps you going? Gosia's answer was quiet, yet full of conviction.

“Working with people is what drives me. It allows me to create real change and to understand the problems on the ground, not just think about them from afar. Listening to human stories is essential; it’s where I learn what really matters.

“Communities themselves are incredibly brave. By providing legal tools, I can support them, and when they succeed, the victory is partly mine, but it truly belongs to them.”

It’s the kind of answer that stays with you. In a Europe often distracted by bureaucracy and short-term gains, here was someone whose work is rooted in fairness, justice, and tangible outcomes for the everyday lives of people and the places they inhabit.

Gosia’s work is more than just a job; it’s a commitment. She, along with her colleagues, supports communities who struggle to be heard, stands up for those whose rights are overlooked, and fights for the health of both people and the environment.

Talking with her, and writing about the Galicia case, learning about the everyday heroes in the community, Pablo, Mercedes – a local resident who dared to raise her voice - and others, I am reminded how rare that quiet, determined dedication is, and how necessary it remains – now more than ever.

“Ultimately, my goal is to leave the world better than I found it. Being results-oriented and motivated by human stories, I aim to use law to create tangible change, protecting health and the environment for future generations,” she concludes.

In Galicia, people’s very being, and that of their loved ones, was at stake. Standing up was no longer a personal choice; it was a necessity. Of course, taking a stand in the face of giants such as the state is never easy, and many across Europe are unable to do so, not for lack of courage, but because the barriers are immense. Yet when communities can act, as Gosia says, it is incredibly brave. In a world where the burden of pollution, industrial harm, and environmental degradation falls heaviest on those with the least power, the courage of ordinary people, guided by steadfast expertise like Gosia’s, offers hope and a reminder that justice, the environment, equity, and wellbeing are inseparable.

Inspired by this story?

Connect with Gosia to follow her work on LinkedIn.

Find out more about the work of ClientEarth.

Photo ©Víctor Luengo / Amigas de la Tierra

Ruth Thomas

Ruth joined the EuroHealthNet team in April 2022 as Communications Officer.

She holds a BA Hons degree in Print Journalism from the University of Gloucestershire (UK) and has worked in the not-for-profit sector for over ten years. Ruth has applied her communication skills to a number of positions including for an energy trade association in Brussels and as part of a National Research Network (Sêr Cymru / Stars Wales), where she was based at a UK university.